It's Gotta Be Da Shoes

As technology advances, so too does performance for the world's best track-and-field athletes.

If you have been paying attention to track and field this year, you’ve probably noticed something pretty strange happening in the mid- and long-distance events. Across the whole set of these events, there have been some unbelievable times run this year. These performances have been highlighted by a slew of world records, some even falling within the same week for a single event. But, world records happen; what has really made these events feel special this year is the unbelievable times being run behind the top performances.

This begs the question:

Why are the times are getting faster?

On the one hand, one could argue that the extended time away from racing imposed by the COVID-19 pandemic has been beneficial. Athletes have been able to focus on their training, especially the mid- and long-distance runners who benefit so much from being able to build up their aerobic fitness by running high levels of mileage.1 But, if this is the whole story, we should be seeing the same types of across-the-board gains in the other event groups.

This fact should push us to consider whether there have been any mid- and long-distance specific changes over the last year. And, wouldn’t you know, there has been one pretty big change! Last year, Nike released a brand new racing spike for the 800- through 10,000-meter track races called the Nike ZoomX Dragonfly. These shoes take advantage of Nike’s latest innovations in foam and material science to build a responsive, lightweight, but rigid spike. Anecdotal evidence from those lucky enough to either be given a pair or be able to buy them suggests that these latest advances are the real deal; Nick Willis, an Olympic medalist from New Zealand, claimed the shoes would give an elite athlete a 1-3 second performance improvement per mile.

Developing this type of new shoe technology and shifting the competitive landscape is not a new phenomenon for Nike. For years now, Nike has been pushing the limits of running technology. In 2017 they released the Vaporfly 4%, a shoe for marathon racers that the company claimed could return about 4% more energy to racers as they ran. Iterations on this base model have continued with the Vaporfly Next% and Vaporfly Next% 2.2

Could the Dragonfly spikes, as well as all of the alternative super spike offerings from Nike’s competitors, be leading to the deep performance gains we’ve seen in the mid- and long-distance events this year?

Let’s dive into some data to find out.

Why not subscribe so you don’t miss out on other analyses like these?

Shifts in Performance

As a first step, we need to make sure that our eyes are giving us a good read of the situation. Are the mid- and long-distance runners, as a group, really running faster this year than in prior years?

We can answer that question by looking at the distribution of times this year to the distribution of times in prior seasons. For this analysis, I will be comparing the 2021 performances to those from 2008-2019.3

In the animation below, we can see how the top 250 performances in the major Olympic events from January to June of each year are distributed. In each frame, the blue distributions represent the performances from 2021 and the salmon-colored distributions represent those from 2008 through 2019.

For the distance events, the blue distributions fall to the right of the salmon-colored distributions, indicating that the performances this year have generally been better, on average, than those in the pre-pandemic time period.

However, the distributions for the sprints, hurdles, jumps, and throws are less consistent. In the sprints, the distributions for each time period are very similar, if not identical in some cases. In the field events, the patterns are less consistent. Even so, we see that in most cases, the performances in 2021 have either been very similar or, if anything, generally worse.

We can also see that the time-period differences appear to be larger for women than for men. This would align with the anecdotal evidence, which has called attention to the surprising depth in the women’s mid- and long-distance events. Going into the Olympics, we had seen many of the top performances in the world this year across the distance events come from women who failed to earn a selection onto their national teams.

Altogether, this basic evidence supports the eye test! Performances in the distance events really are better, on the whole, this year than in the period before the pandemic, while none of the other event groups have seen consistent improvements.

Accelerating Improvement

Beyond just comparing the distribution of performances, we should consider just how much better these times are than we have seen in other years.

One way to think about these performance shifts is to consider how much better or worse a certain performance is than the performance in the same rank from the year before (or two years before in the case of 2021). This approach may not be the most common way to think about performance. But, it does make sense.

Track and field athletes compete on an Olympic cycle, meaning that they have one Olympic meet every four years and a World Championship meet the year before and after the Olympics. These three meets comprise the highest championship level in the sport, but the Olympics shines above the other two because it offers the greatest opportunity for fame, monetary rewards, and legacy-building results. As such, we should expect to see performances within a given spot on the leader board vary based on where in the current Olympic cycle they fall, with the greatest year-over-year improvement in Olympic years as athletes rush to hit Olympic qualifying marks and make their national teams.

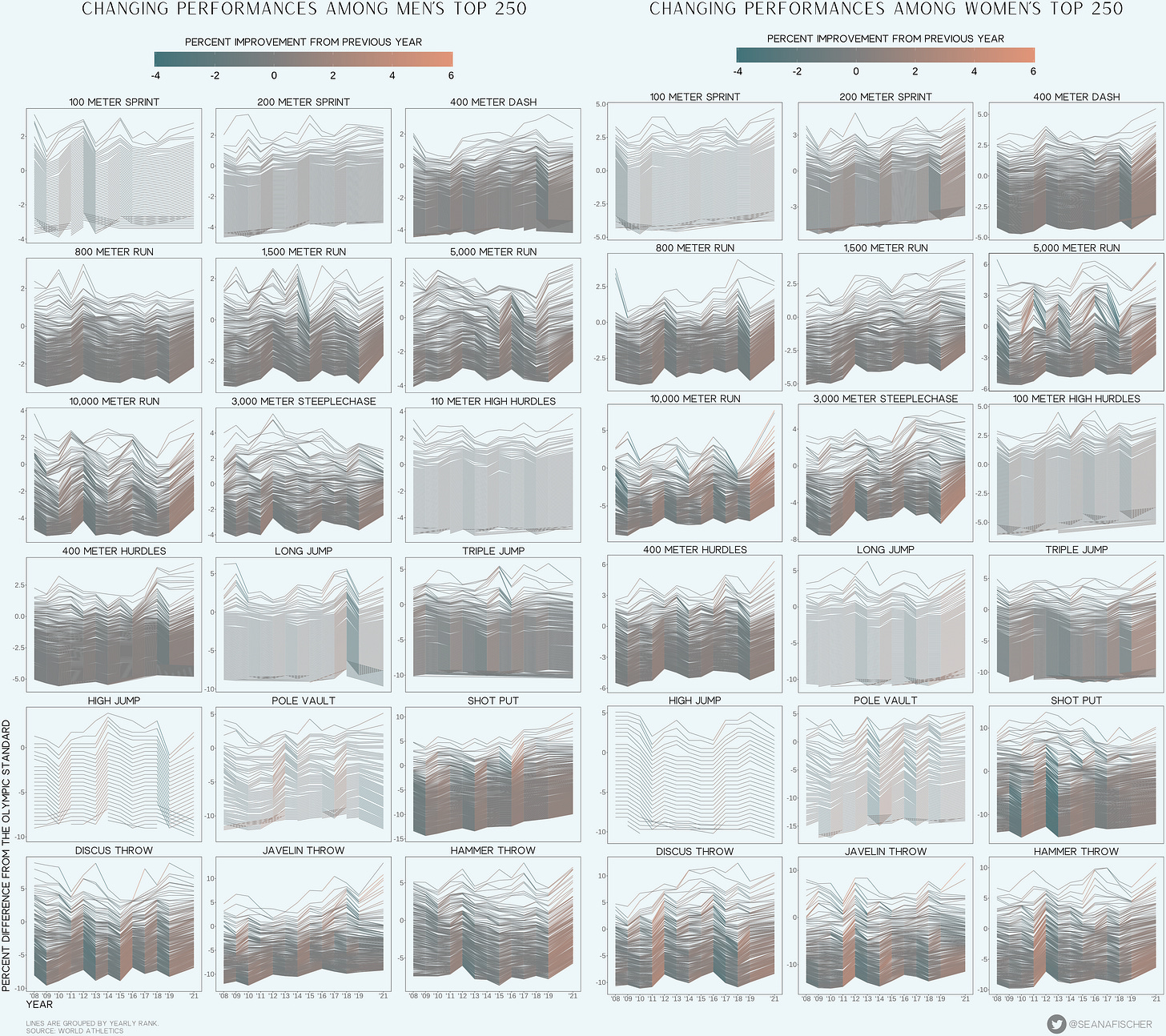

We can see just this pattern over the 2008-2019 period in the two visuals for men and women below.

Across all the events in the 2008-2019 period, we can see the expected cyclic pattern. Every Olympic year, performances deep into the leaderboard improve more than we see in the non-Olympic years at a relatively constant rate. But, in 2021, the magnitude of the year-over-year improvements from 2019 shoot way up. We can see these bigger changes in the darker red tones at the end of the graphs and the large bends in the lines moving from 2019 to 2021 for the mid- and long-distance races. Note that the strong year-over-year improvements run all the way through the top-250 performances.

These graphs give us more compelling evidence that our eyes have not deceived us. The distance events have experienced a shift in performance distinct from those in the other event groups. Runners in these events have wildly exceeded the normal Olympic cycle improvements we’ve seen in the 2008-12 and 2012-2016 periods. At the same time, performance improvements have generally not accelerated in the other events.

Just How Good Are They?

These visualizations give us a very helpful view of the trends over time, but do little for us in terms of actually putting a firm number on the benefit the shoes are providing.

To get such a number, I estimated difference-in-differences (DiD) models for the men and the women. I will be going into more detail about these models in the follow-up post later in the week that explains the methods and code behind this analysis, but for right now you should know a few things about DiD models.

First, DiD models are intended to help researchers figure out the causal effect of some intervention when it occurs in a natural setting outside of the lab. They do so by comparing a treated group before and after treatment to a control group, or a group that did not change, before and after treatment. By comparing the difference between these two differences, we get an estimate of the effect of treatment alone that is less biased by features we cannot actually measure. As in most parts of life, less bias here is good!

Second, these models have a few assumptions. Most importantly, we have to assume that the treatment groups (the mid- and long-distance runners) and the not-treated group (all the other athletes) had similar trends before treatment and would have continued to have similar trends if treatment had never been delivered.4 This assumption, in particular, may not be plausible, as Nick Willis noted on Twitter that athletes not in the distance events have had more accounts of having reduced access to training resources over the pandemic than their distance-running counterparts.

Third, we can estimate these models using basic regression techniques, but also more advanced forms of regression as well. Here, I’ll do a little bit of both for both men and women.

Let’s begin with the simpler models. These simple models make all of the standard DiD assumptions (i.e. that the distance runners and everyone else share a similar trend pattern before treatment), as well as the assumption that the effect of treatment is the same across the entire treatment group.

Each model will estimate the percent difference from the Olympic qualifying standard for the Nth ranked athlete in an event. For example, we will use these models to estimate the percent difference from 10.05 seconds for the best 100-meter runner and the percent difference from 1:45.20 for the 100th best 800-meter runner in each year.

For the men, the effect of the super-shoes is a modest 0.90 percentage points. That means that the change from the 2008-2019 in 2021 for the nth best performer in one of the distance races was, on average, 0.90 greater than the same change for an athlete in one of the sprints, hurdles, jumps, or throws. This effect might feel small when we see it in percentage-point units, but it represents a pretty substantial improvement. In the 100, this effect would be comparable to a 10.05-second 100-meter performance dropping down to a 9.96-second performance or a 13:30 5,000 meter performance cutting down to a 13:22.

For the women, that difference was even larger at 1.40 percentage points. Again, this means that the change from the 2008-2019 window to the 2021 season was about 1.40 percentage points higher for distance runners than athletes in the other event groups. To put this bigger jump in its own context, it would be like an 11.15-second 100-meter performance going down to a 10.99-second performance or a 15:00 5,000 meter performance dropping to 14:47.

There is no doubt about it; these effects are substantial! If these performances all fell in the same race, we would not describe them as being close to one another. In this way, we can say that the shoes definitively work.

But, you might be wondering, as Chris Derrick did when I shared the first results for the men, whether the effects of the super shoes change between the best runners and those farther back in the performance pack.

Luckily, we can answer this type of question by estimating a more complex DiD model!

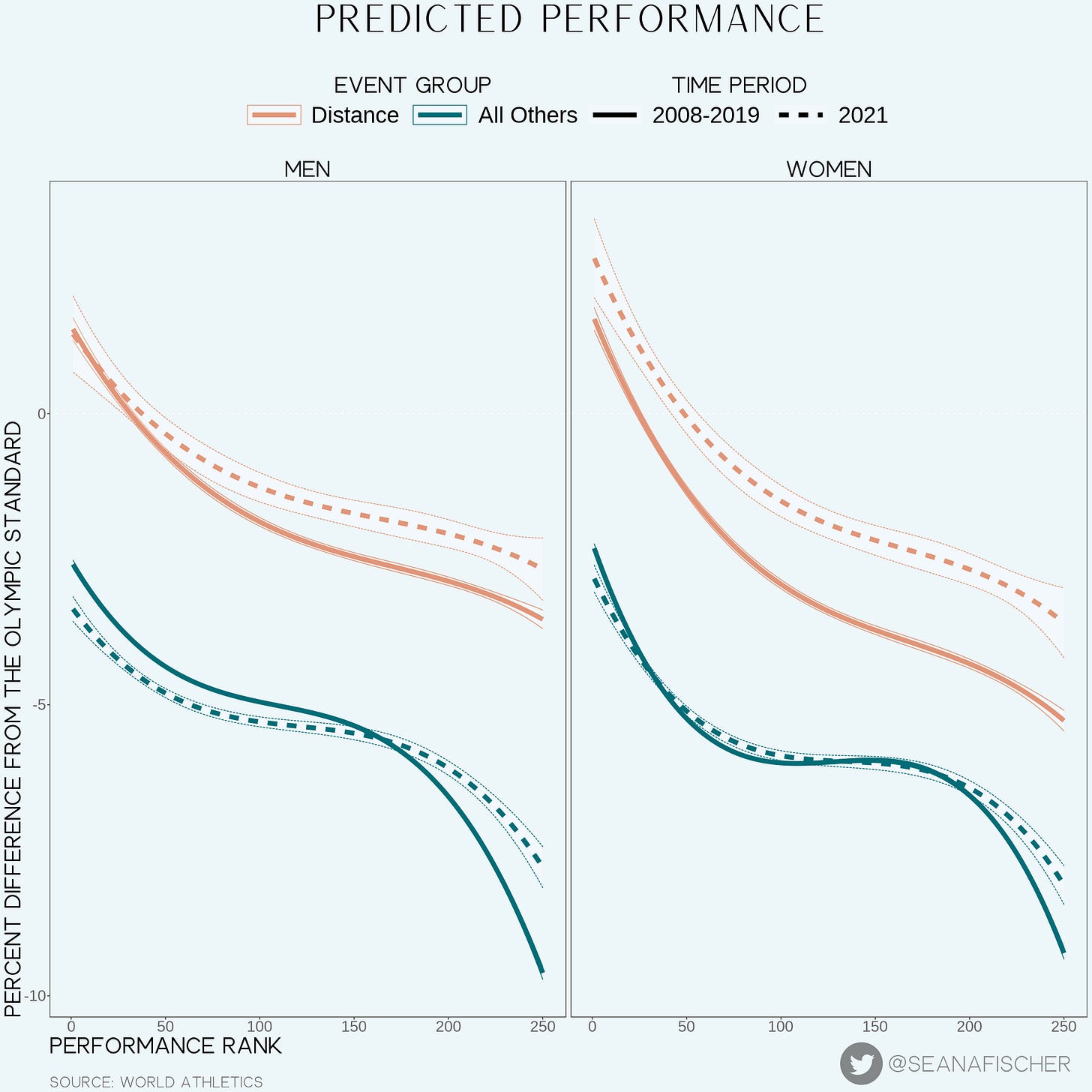

The more complex DiD model evaluates whether the super shoe effects vary depending on the rank of the performance in a non-linear fashion.5 This complexity allows us to test whether the effect changes in non-constant ways depending on how deep into the performance list we go. For example, the effect might be smaller for the top 10 or 20 ranks than the next 50. However, adding this extra complexity makes it hard to identify a single numerical estimate of the effect. Instead, we will have to look at some graphs to see how the predicted performance improvements compare between groups.

Introducing this complexity for the men and the women, we see that in the pre-super-shoe era that distance performances decrease in quality at a fast rate to start before slowing as we look deeper into the performance list. For the non-distance events, performances decline quickly to start, level off for the middle ranks, and then tail off strongly again for the back third.

But, we can see some important changes in the predicted performances of distance runners in 2021. First, for the men, the rate at which performances decrease as we look deeper into the list slows. As a result, the performances in the middle and back of the top-250 are significantly greater in 2021 than in the 2008-2019 period. Second, for the women, the same slower rate of decline is occurring, but is also combined with better quality performances for the best runners. The end product is across-the-board improvements that get larger for the middle and back-end performances. Notably, though, we see no meaningful deviations in the shape of the performances in the 2008-2019 period and 2021 for the non-distance events.

These results leave us with a few important conclusions:

The shoes appear to have a real and meaningful effect on performances in the distance races; and

These effects are larger for performances farther away from the best in the world.

The ultimate result is a shrinking of the gap between the best distance runners and those chasing them. In 2021, the 100th-best distance performances have been similar to the 50th-best performances from 2008-2019. Anyone running in the distance events without the shoes is likely to be running with a severe handicap.

Distance Running Going Forward

A shrinking gap between the best distance runners and those chasing them on the world leaderboards has some important implications for the athletes and their support teams.

Most notably, it means that the best distance runners in the world, with few exceptions, have smaller margins for error when they toe the line. Where in the past these top competitors may have been able to survive some poorly executed race strategy or simply not physically feeling their best on any given day, these runners need to execute as close to perfect as possible because the rest of the elite distant-running field is now more capable of ever of racing with them. We’ve seen this across the Diamond League in the first half of the 2021 season; time and again, runners at the top of the leaderboards or former world champions have lost to runners who did not even end up qualifying for their countries’ Olympic teams.

However, athletes and those working with them likely need to also hold some other considerations in hand. Among these are the potential for new injuries. In talking with track-and-field insiders who have been able to get ahold of the new spikes, they have repeatedly emphasized the fact that the Nike Dragonfly spikes and others like them place new strains on the lower body because of their stiffness. We will want to pay attention to injury announcements from athletes and try to compare to rates before the introduction of the new spikes.

Of course, some athletes may choose to race less if they find it easier to run fast. Compared to injuries, this metric may be easier to track. If so, will we see athletes take more opportunities to race outside of their main event? Much of the decision-making process in this regard may depend on how athletes and their sponsors structure their contracts, a topic in which I am not an expert.

What to Keep Looking Out For

With the Olympics wrapped up, the astute fan should pay attention to what types of spikes competitors use in the last portion of the season, especially if they are in the running events. This year, Nike has released a new set of sprint spikes and a new long-jump spike that builds on the technology in the Dragonfly spikes. However, these shoes were rolled out only part-way through the first half of the season and were not universally adopted, even by the time countries hosted their Olympic qualifying meets. If competitors in the shorter distances and the long jump begin wearing these new offerings, we should see similar performances changes in these events as we have seen in the 800 and up before the Olympics.6

The astute fan should also pay attention to the brands sponsoring each competitor. Nike was the first to launch a super spike for the distances, but other brands, such as Asics, have managed to build and release successful options. Others are allowing their athletes to wear the Nike options, especially if the Nike branding is covered or removed. However, some companies, like Under Armor and Adidas, have informed their athletes that they are not allowed to wear Nike shoes, even if a comparable within-sponsor option does not exist yet. Will these brands still prohibit their athletes from wearing the best available options, even if it means the athletes have lower chances of winning a medal? We can follow up on this question in a later post.

At the Olympics, we saw incredible times in almost all of the running events, with world records recorded in the men’s and women’s 400-meter hurdles. The quality of the performances has been partially attributed to the actual track at these games, but some of the athletes have called attention to the shoes. Karsten Warholm, the gold medalist and world record holder in the men’s 400-meter hurdles, specifically called out silver medalist Rai Benjamin for wearing Nike’s new shoes: “He had those things in his shoes, which I hate…I don’t see why you should put anything beneath a sprinting shoe…In middle distance I can understand it because of the cushioning. If you want cushioning, you can put a mattress there. But if you put a trampoline I think it’s bullshit, and I think it takes credibility away from our sport.”7

As fans, we will eventually have to take a stance on this issue. Two competing elements in sport are advancing technology and constant comparison to the past. Normally, the technology moves slowly enough that these comparisons looking back are reasonable, or arguably reasonable. But the new spikes seem to represent a large breach from history for the events that have adopted them. That can be ok, but will require us, as fans of the sport, to change how we contextualize this new era of heightened performances.

If you enjoyed the post, please share it with friends and subscribe to receive future analyses!

Some might also extend that the potential reductions in drug testing might have also made it easier for athletes to push their pharmacological programs as well.

The New York Times independently verified the benefits of these shoes in two different analyses.

2020 is dropped here for rather obvious reasons.

If there is enough interest I can do a deeper dive into how well these data meet the assumptions in another post.

Again, I’ll share more about this modeling process later in the week!

I’ll follow up at the end of the outdoor season to see if the second half looked any different from the first!

Of course, it is worth noting that Warholm raced in specially designed shoes with carbon fiber plates and a thin layer of advanced foam.